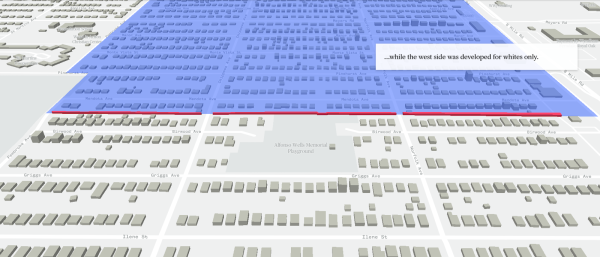

In recent decades, Metro Detroit has seen strides in urban development. However, in the 1930s to 1960s, development came to a stand still, and in fact, receded in certain areas. Much of these concentrated recessions can be attributed to the harmful practice of redlining: a discriminatory housing practice that left minority communities, primarily Black Americans, in financial turmoil. A basic zipcode determined the opportunities, services and education available to minority residents and ultimately dictated the life of families for generations to come.

While redlining is defined by Oxford dictionary as to “refuse (a loan or insurance) to someone because they live in an area deemed to be a poor financial risk,” the practice has had major impacts on the advancement of Black and other minority populations’ ability to thrive from education, career and healthcare perspectives. Certain neighborhoods, typically those with high populations of minority residents, were “redlined” to signal to investors that these communities are “hazardous” to invest in, therefore withholding opportunities that would be offered to non-redlined counterparts. Denial of credit and insurance, resources that are often integral to a citizen’s advancement in society, to people from redlined communities were common examples of services unjustly withheld, solely due to demographic.

Legislation, such as the Federal Housing Policy from the 1930s to the 1960s, made it easier for white families to buy homes, while actively discouraging Black families from doing the same. Home equity is one of the cornerstones of building generational wealth; however, due to redlining, many homes in redlined areas had decreased value, making it much harder for minority homeowners to accumulate generational wealth, often used to help children achieve higher education.

A study conducted by the Annenburg Institute for Social Science and Public Policy at Brown University found that the lines drawn nation-wide impacted district-level and school-level funding, student racial diversity and student performance negatively. Specifically, the results of the study indicated that “schools and districts located today in historically redlined D neighborhoods have less district per-pupil total revenues, larger shares of Black and non-White student bodies, less diverse student populations, and worse average test scores” compared to their non-redlined counterparts.

Sydney Barosko, science teacher at Troy High School and advisor of the school’s Black Student Union chapter comments on how “redlining has had long standing effects on property values and opportunities for people in the neighborhoods who were redlined, which in turn gives them less of a chance to leave that community, achieve higher education, attend university, graduate level degrees, ultimately affecting whose voices are in the room.”

While the illegal practice of redlining was outlawed in 1968 by the Fair Housing Act with subsequent legislation such as the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act of 1975 that protected many communities from redlining, the discriminatory housing practice still has long lasting impacts that continue to disadvantage minority populations.

Mburu Karimi, senior at Troy High School and President of the school’s Black Student Union chapter says that “the American democracy posters up as equality for all, and in theory, everyone should get the same public schools, healthcare and resources. However, redlining keeps populations who are already disadvantaged down,” and adds that redlining still impacts many communities today.

The American democracy is rooted in principles of equal opportunity, yet redlining undermines this principle by limiting opportunity by neighborhoods. Kevin Flaherty, history teacher at Troy High School, believes that “redlining is one of the many examples of inequality that is systematic, and any type of inequality weakens a democracy, especially when it comes to equal opportunity, which is supposed to be our founding ideas. Redlining shows how we betrayed this idea, and for generations.”